The excellent analysis below from the CALIFORNIA POLICY CENTER (and my write-up) is a “must read” — especially for Californians. Unions rule. More specifically, GOVERNMENT unions rule.

Our CA state and local public employee labor unions collect about $900 million in dues annually. How does that spending affect politics? Consider:

Most projections of public employee labor union political power are limited to FEDERAL and sometimes STATE government REPORTED union spending. While it’s a huge factor (especially at the state level), it is DWARFED By government union political spending at the local level.

How much of the $900 million in annual CA public labor union dues is spent on politics? Nobody (outside of the union bosses) knows.

It’s carefully concealed by the unions — with government complicity. There is no required disclosure. Indeed, there’s even no AUDIT of the union figures found on the IRS form 990’s. Whatever is revealed is controlled by the unions.

And control is the name of the game. On the local level, these government labor unions are the biggest spenders on most local elections. The union bosses well understand that — unlike legitimate private labor unions — public employee labor unions usually get to decide who gets elected as their “CEO’s.” The unions pick the politicians with whom they “negotiate.” They are not always successful — but far more often than not — the union bosses get pretty much what they want.

Let’s go back to my rhetorical question about how much of the $900 million is spent on politics. Unions fess up to about 25% in their unaudited disclosures. A conservative estimate is over half. A more educated guess would be 70% or more. Awesome!

Even with the Janus decision, CA government unions probably will collect well over $600 million in dues a year. Their control of local politics will remain largely intact — until we ban such unions — and contract out every possible government job.

CALIFORNIA POLICY CENTER

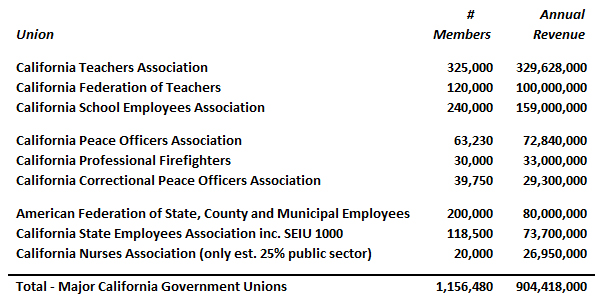

California’s Major Government Unions Collect At Least $900 Million Per Year

In the wake of the Janus ruling, it is useful to estimate just how much money California’s government unions collect and spend each year. Because government unions publicly disclose less than what the law requires of public corporations or private sector unions, only estimates are possible.

The primary source of information comes from Form 990s that government unions must provide to the IRS each year. Copies of these 990s can usually be found on Guidestar.org; sometimes they are also available on the union websites. While these 990s are useful, to put together reasonably accurate estimates of total government union revenue they require careful analysis and supplemental information from elsewhere. With these limitations noted, here are summary estimates of how much money California’s taxpayers are providing to government unions, who withhold their dues directly from the payroll departments of public agencies.

PUBLIC EDUCATION UNIONS

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2016 there were 422,248 “full time equivalent” teachers employed in California’s K-12 system of public education. In California’s UC and CSU systems of higher education, there were 30,005 faculty instructors. Support staff in the K-12 system numbered 239,726 employees, and in higher education they numbered 40,770 employees.

The largest union focused on K-12 teachers is the California Teachers Association (CTA), easily the largest and most powerful union in California. Their most recent financials, for the year 2015, show declared revenue of $190 million, with $178 million of that declared as dues from members. This, however, greatly understates the power of the CTA.

Not only is the CTA a branch of the nationally focused National Education Association, but the CTA in turn is comprised of local chapters. These local chapters retain a significant share of dues revenue, which they report on their own 990 forms. The CTA chapter United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA), for example, declared membership dues of $38.9 million in 2015.

Collecting exact financial data including dues revenue for all CTA chapters would be possible, but not easy. Including the behemoth UTLA, the CTA has 1,100 chapters, plus the California Faculty Association and 42 chapters in the Community College Association. But making a reasonable estimate is possible based on the CTA “Fact Sheet” where they declare a membership of 325,000, combined with the UTLA’s disclosure of their “new dues structure,” wherein full time members pay $1,014 per year.

Based on this information, one may estimate the total annual dues revenue of the CTA and its affiliates at around $330 million per year. While some members may not pay the full dues, which might lower this estimate, the CTA and affiliates have other sources of income including investment income. For example, at the end of 2015 the CTA declared net assets of over $190 million, and the UTLA declared net assets of $28.6 million.

While the CTA is huge, it is not the only union player in California’s system of public education. A much smaller but still very large and powerful teachers union active in California is the California Federation of Teachers (CFT), a branch of the American Federation of Teachers. On their “Who We Are” page, the CFT claims a membership of 120,000, spread over 145 local chapters.

Just as with the CTA, precisely calculating the total dues revenue of the CFT is nearly impossible. Moreover, some of the AFT’s claimed chapters, the UTLA in particular, are actually quasi-independent unions that are affiliated with the CTA and the CFT. But based on their membership claims, and taking into account these complicating factors, a reasonable estimate of the total dues revenue for the CFT and their direct local affiliates is probably around $100 million.

The power of the unions in California’s system of public education doesn’t stop with the CTA and CFT, however. There is also the California School Employees Association (CSEA), claiming membership of 240,000 mostly “classified” (non-instructional) support staff. The CSEA is divided into “Areas” and “Regions” which is their equivalent of local chapters. Their 990 reports a 2015 revenue of $67.2 million, but it is unlikely their total revenue is this low. Using a few assumptions this can be tested.

If you assume CSEA dues are 2% of pay, which is typical, and you reference the average pay of what the U.S. Census defines as California’s “Education – Elementary and Secondary – Other,” an informed estimate can be made by assuming 50% of CSEA members work full-time, and 50% of them work part-time. On that basis, the full-time CSEA member would pay $993 per year and the part-time member would pay $335 per year. This equates to annual dues revenue of $159 million per year.

In summary, subject to the limitations in the available data and what appear to be reasonable assumptions, California’s public education employee unions, the CTA, the CFT, and the CSEA, altogether are probably collecting around $589 million per year.

PUBLIC SAFETY UNIONS

The difficulties inherent in estimating revenue for public education unions are equally present when trying to estimate revenue for public safety unions. The firefighter unions and police unions are for the most part decentralized, with advocacy organizations in Sacramento collecting a small portion of the total revenues of the various locals.

For example, The Sacramento based California Peace Officers Association (CPOA) only declared revenue of $1.7 million in 2016. The Sacramento based California Professional Firefighters (CPF) only claimed revenue of $3.6 million in 2016. But these two organizations operate more as coordinators for the efforts of their affiliates throughout the California. The big money is collected locally.

The Los Angeles Police Protective League illustrates this point. With revenue in 2016 of $11.6 million, they financially dwarf their counterpart in Sacramento. When their membership dues, $10.4 million, is divided by their 9,900 membership, their average dues can be estimated to be $1,152 per year.

Extrapolating this estimate of average dues to the total number of full-time police officers in California, 63,230, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as “Police Protection – Persons with Power of Arrest,” it is reasonable to estimate the California’s total police union dues revenue is around $72.8 million per year. This number could be larger, based on the Public Policy Institute’s recent analysis which states “In 2015 there were more than 118,000 full-time law enforcement employees in California; roughly 77,000 were sworn law enforcement officers (with full arrest powers) and 41,000 were civilian staff.”

Firefighter unions, also decentralized into locals, defy easy compilations of total revenue. A conservative estimate of their average dues would be to assume they are comparable to police union dues, $1,100 per year. According to the CPF website they “claim over 175 IAFF locals as CPF affiliates, serving more than 30,000 paid professional firefighters. ” This is consistent with the U.S. Census data, which estimates “Fire Protection – Firefighters” at 28,907 employees” and “Fire Protection – Other” at 4,182 employees.

Based on these variables, total annual revenue for all affiliates of the California Professional Firefighters union is estimated to be around $33 million per year.

The other public safety union, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association, appears to be a centralized organization, claiming 39,750 members. Their 990 for 2016 declares total revenue of $29.3 million, This implies an annual dues of $1,088 per year, which is consistent with other unions.

In summary, California’s public safety unions, the CPOA, the CPF, and the CCPOA, along with their local affiliates, altogether are probably collecting around $135 million per year.

OTHER PUBLIC SECTOR UNIONS

No survey of California’s government unions is complete without taking a look at three very large and influential unions – the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the California State Employee Association (CSEA, not to be confused with the California School Employees Association), and the California Nurses Association.

With these unions as well it is difficult to gather accurate compiled data, because in each case dozens if not hundreds of local affiliates are filing separate 990 forms. AFSCME California, for example, includes the following:

Council 36 – extending across Los Angeles to Orange County to San Diego representing more than 55 autonomous Local Unions whose members work in local government agencies and nonprofit organizations.

Council 57 – representing workers in schools and community colleges, transit agencies, public works and services, clinics and hospitals, and water and wastewater facilities throughout Northern California and the Central Valley, as well as the health and social service professionals in corrections facilities across California.

Employees Association of the Metropolitan Water District, Local 1902 – representing the workers of Southern California water districts including accountants, designers, electricians, engineers, environmental specialists, inspectors, IT, mechanics, meter technicians, pipelayers, and PR specialists.

Management and Professional Employees Association of the Metropolitan Water District, Local 1001 – representing the management and professional employees of the the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

United Nurses Associations of California/Union of Healthcare Professionals (UNAC/UHCP) – representing over 29,000 registered nurses and other health care professionals, including optometrists; pharmacists; physical, occupational and speech therapists; case managers; nurse midwives; social workers; clinical lab scientists; physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

United Domestic Workers of America, Local 3930 (UDW) – representing nearly 98,000 in-home support services (IHSS) workers in 21 California counties who take care of Californians with disabilities, the sick, and the elderly.

United EMS Workers, Local 4911 – representing approximately 4,000 private sector emergency medical services (EMS) workers in California whose mission is to raise standards in EMS and protect services for the public.

Union of American Physicians and Dentists, Local 206 (UAPD) – representing doctors working for the State of California, California counties, non-profit healthcare clinics, and in private practice.

University of California Employees, Local 3299 – the University of California’s largest employee union, representing more than 24,000 employees at UC’s 10 campuses, five medical centers, numerous clinics, research laboratories and UC Hastings College of the Law.

Public Employees Union, Local 1 – representing public employees in Contra Costa, West Contra Costa, Merced, Sutter/Yuba, and El Dorado counties.

Calculating the total dues revenue of AFSCME California’s ten major networks of union locals is difficult; precisely estimating their total number of members is impossible to acquire via publicly available information. Based on the information provided on the websites of these locals, total membership can be guessed at. Four of the AFSCME California networks disclose their membership (in italics, above), totaling 155,000. Examining the descriptions of the other six networks suggests a conservative estimate of an additional 45,000 members. Assuming annual dues revenue of $400 per year per member, AFSCME is collecting $80 million per year. That’s probably on the low side.

The California State Employee Association is an agglomeration of three principle unions, the California State University Employees Union with revenue in 2016 of $7.1 million, the Association of California State Supervisors, with 2016 revenue of $3.4 million, and the powerful Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1000, with 96,000 members and 2016 revenue of $63.2 million. Altogether the unions that comprise the California State Employees Association in 2016 collected revenue of $73.7 million.

Including the California Nurses Association among a survey of public sector unions requires some explanation. It clearly would be inaccurate to claim that all their members work in the public sector. For the purposes of this compilation, we will assume that 25% of them work for public healthcare facilities, based, for example, on their penetration of the UC system healthcare networks and many of California’s county medical centers. The CNA claims membership of 80,000 and for 2016 their 990 declared revenue of $107.8 million.

In summary, California’s other major public sector unions, AFSCME, the CSEA including SEIU Local 1000, and the CNA (est. public sector portion at 25%), along with their local affiliates, altogether are probably collecting around $135 million per year.

CONCLUSION

Based primarily on publicly disclosed 2016 form 990s along with information obtained from their individual websites, in aggregate, California’s major public sector unions are estimated to be collecting over $900 million per year.

Because there are undoubtedly smaller and less visible public sector unions operating in California, this number may be conservative. The number is also possibly understated because when making assumptions, conservative estimates were always applied. This was the done when estimating average membership dues in nearly all cases, and also with respect to total membership.

California’s Public Sector Unions

Total Membership and Revenues – 2016 Estimates

It would go beyond the scope of this analysis to speculate as to what impact the recent Janus ruling will have on government union membership and revenues, or to ponder the degree and kind of political influence of the three major blocks of unions; teachers, public safety, and public service.

It is relevant, however, to emphasize that the reach of these unions, because almost all of them are highly decentralized, extends to the finest details of public administration, into the smallest local jurisdictions. When recognizing the profound statewide impact of public sector union political agenda, it is easy to forget that fact, and the implications it carries for virtually every city, county, special district, or school district in California.

Ed Ring co-founded the California Policy Center and served as its first president.

* * *