This is the first in a series of stories about the Japanese forced in to labor camps in Siberia immediately following the end of WWll.

Seventy years have passed since World War II ended, but for many Japanese soldiers captured and deported to Soviet detention camps in Siberia, the story needs to be told.

At the time of Japan’s surrender to Allied forces on August 15, 1945, most of the rest of the world thought it was the end of World War ll. However, another horror was just beginning for more than 600,000 soldiers of Japan’s army; they were deported to Soviet labor camps in Siberia known as Shiberia yokuryū, the Siberian Internment. Most were held for years, and forced into labor and reeducation campaigns. More than 60,000 of the captured Japanese soldiers died.

Most Americans are unaware that the Soviet Red Army imprisoned more than a half-a million Japanese soldiers and civilians immediately following the end of World War II in 1945. The Red Army deported the Japanese to labor camps in Siberia, where many remained imprisoned until 1956, despite Japan’s efforts to gain their release.

And it’s been a little-discussed topic even in Japan.

“Japanese gulag returnees themselves were never silent: just ignored, at least until they began to organize themselves into a number of (sometimes fractions of) communities of memory,” according to Andrew E. Barshay, a University of California, Berkeley Professor, and only one of a handful of researchers on this topic outside Japan.

Japanese in Siberia

Haruko Oshima Sakakibara, a lecturer of Japanese in East Asian Language and Culture at University of California, Davis, is telling the stories of the Japanese soldiers, just as August 15 commemorated 70 years since the end of World War II.

Sakakibara grew up in Japan after the war, and said many families were still in deep sadness and pain after the loss of their loved ones. Her uncle was interned in Siberia. And while he eventually made it back to Japan, “the rest of his life was covered with a dark shadow until he passed away of lung cancer,” she wrote. She explained that “patience with silence” is viewed as dignity in the Japanese culture. “They are not taught to ask questions because the conformity has been an important part of the social order in the society that started with the “cooperation” for rice farming in ancient time.”

Haruko Sakakibara created the bilingual website, “Japanese in Siberia” to tell the stories of the now-aging and elderly Japanese men, largely forgotten, or who were a part of history many in the world never heard of. “In contrast to Japanese American Internment that happened in California, this war history should be known,” Sakakibara said in an interview. “The war caused a lot of sadness in Japanese homes as well.”

Sakakibara, born in Japan, married Jonathan Sakakibara, an American citizen, and has lived in the U.S. for more than 30 years. She has interviewed many of these men, and is telling their stories, in English and in Japanese.

Peter Sano

Peter Iwao Sano’s story is different than others. Sano was born in Brawley, California in 1924. At the behest of his parents, at age 15 he Sano was adopted to his uncle and aunt’s family in Japan and gained Japanese citizenship. However, Sano was drafted into the Japanese army during WWII, and then was captured and taken to Siberia after WWII. Sano’s family did not know he was sent to Manchuria or that he was a prisoner in Siberia until well after the war was over.

In his interview with Sakakibara, Peter Sano told of the suffering the Japanese experiences while imprisoned in Siberia. “We suffered most with the shortage of food, the cold weather, and the hard work,” Sano said. He said the first winter of 1945 in Siberia was the coldest weather, and he was working at the coal mine. “I was on the night shift which was from 4:00 p.m. to 12:00 midnight,” Sano said. “When you come back to camp, it is past midnight. That’s when we walked through the gate. There was a thermometer hanging there, and I didn’t see it but the soldier next to me who passed said it was minus 63. And that’s in centigrade. So in Fahrenheit, if my calculation is correct, that was minus 79 Fahrenheit.”

Sano said the shortage of food brought about terrible suffering. “I remember in Japanese saying, ‘Bushiwa Kuwanedo takayoji,’ which means, a warrior even though he may be hungry, he uses a tooth pick to say ‘have eaten enough,’ and never admitted the fact that they were hungry because that was not a good warrior,” Sano said. Sano said however, that the warrior mentality was abandoned, and they fought over food, and even stole food. “The shortage of the food was not the way that the Soviets, it was not the methods that they were making us suffer. They themselves did not have food,” explained Sano.

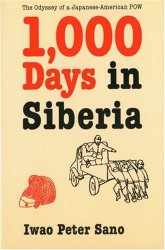

Sano became critically ill with Malaria toward the end, and eventually made it out of Siberia, and came back to the United States, where he regained his American citizenship and settled in Palo Alto. Then he worked as a draftsman of architectural drawing until retirement. Peter Sano is the author of the book, “1000 days in Siberia.”

The reasons the history of the Siberian internment have not been shared, and have been almost “buried” in Japanese history are numerous, according to Sakakibara. She said the primary reason was because of the Japanese traditional cultural value of despising “shame.” “Even though deep wounds existed among the returnees, it was difficult for them to cope with the sense of ‘shame’ for the fact they were imprisoned even though they did not commit any crime,” Sakakibara said. “In their military training, they were educated that ‘death’ was more honorable than ‘surrender.’” Even after facing Siberia, they maintained their silence.

Sakakibara said another reason was the sense of guilt – the guilt of survival. “The ones who made it home had to leave the corpses of their friends who died during the ordeal,” she said. “Their inner difficulties lingered because of the extreme sadness they experienced when their comrades fell and died, and when they could not even make satisfactory tombstones in the frozen land of Siberia. Sometimes they had to go to the next camp, leaving a mountain full of frozen dead bodies behind them.”