I am delighted today to present “The Tao of Jerry” — an outstanding, substantive perspective on our state’s governor, as offered by Claremont Institute scholar William Voegeli. The piece is lengthy, and even that may be an understatement. That having been said, once you have read it, I’m sure you will agree that to edit it down to a shorter length would have been to have lost precious insights into this complex man who is once again atop the Golden State’s political structure. My only reading “tip” for you would be that if you do not have the time to read this at your computer, the essay is available in .pdf format here — so you can print it to read at your leisure.

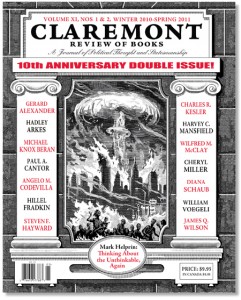

Voegeli is a frequent contributor to one of the most significant and important publications to which I subscribe, the Claremont Institute’s Claremont Review of Books. Here is a great, succinct description of the CRB courtesy of the CI…

The Claremont Review of Books offers bold arguments for a reinvigorated conservatism, which draws upon the timeless principles of the American Founding and applies them to the moral and political problems we face today. By engaging policy at the level of ideas, the CRB aims to reawaken in American politics a statesmanship and citizenship worthy of our noblest political traditions.

Without any further introduction…

THE TAO OF JERRY

By William Voegeli

From The Claremont Review of Books

If Americans had spoken of “red states” and “blue states” in 1958, California would have been a red one. Over the preceding 70 years Democrats had never held simultaneous majorities in both houses of the state legislature. Going into the 1958 midterm elections, the state’s congressional delegation comprised 17 Republicans and 13 Democrats, meaning that 57% of California’s representatives were Republicans at a time when the GOP accounted for only 45% of House members from the other 47 states.

The 1958-midterm elections, however, began California’s transformation into a Democratic stronghold. The party won majorities in both the general assembly and the state senate that year, and has never really relinquished them. By 2012 Democrats will have held simultaneous majorities in both chambers for 50 of the preceding 54 years. Even as the national GOP mounted a surprising comeback in the 2010 midterm elections, noted the New York Times, “[t]he political chasm separating California and much of the rest of the nation grew wider as voters reaffirmed their preference for Democrats.” Democrats won all eight statewide offices, held a U.S. Senate seat, and increased their majority in the state legislature. By one measure, California is now half-again as blue as the rest of the country: while Democrats account for 42% of the members elected to the House of Representatives from the other 49 states, California’s House delegation is 64% Democratic—34 out of 53.

The Democratic gubernatorial candidate in 1958 was the state’s attorney general, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown. His victory made Brown only the second Democrat elected governor in the 20th century, following the single term served by Culbert Olson from 1938 to 1942. Since 1958 the California Democratic Party’s relationship to the governor’s office has been mediated by its relationship to the Brown family business. As Chapman University urban scholar Joel Kotkin points out, except for the Kennedys in Massachusetts no family in modern times has dominated one state’s politics more than the Browns of California. Pat Brown served two terms before losing the 1966 gubernatorial election to Ronald Reagan. After one term as California’s Secretary of State, Edmund G. Brown, Jr.—Jerry Brown—was elected governor in 1974. Jerry’s sister Kathleen was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee in 1994, 12 years after the end of Jerry Brown’s second term. California has had only one Democratic governor not named “Brown” since 1958: Gray Davis, who won the office in 1998 and 2002 before losing a recall election in 2003. Davis, however, got his first job in politics as Governor Jerry Brown’s chief of staff.

Half a lifetime after becoming California’s youngest governor at age 36, Jerry Brown now returns as the oldest person elected to the office at age 72. His victory in 2010 is further evidence that California is a state with a long coastline and a short memory. During his first eight years as governor he found time for three unsuccessful campaigns for other offices—two for the presidency and one for the U.S. Senate. Despite high approval ratings during his first term and a landslide re-election victory in 1978, he ultimately became so unpopular that two Republicans successfully ran against him in 1982, a good year for Democrats generally. Pete Wilson won a senate seat by defeating Brown, while George Deukmejian was elected governor by promising to be nothing like him.

Whether he’s a better old governor than he was a young one will depend, in part, on how much Brown changed during the 28 years between his second and third terms. Familiarity with the unconventional politician described in a 1974 Time magazine cover story as a “tense and introverted intellectual” eventually bred contempt. By 1992, when he offered himself in a third failed presidential campaign as the last honest man in American politics, Mickey Kantor, who had managed Brown’s 1976 presidential campaign and 1982 senatorial run, said Brown had been reduced to “a groping politician looking for the next thing he can exploit.” Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter called him “a chameleon, a character assassin and a first-class cynic.”

Golden State No More?

More important than the question of whether Jerry Brown has changed for the better is the fact that California has, in crucial respects, changed for the worse. Brown takes office at a time of grave fiscal peril. In December 2010 the New York Times reported that many bond market experts “fear that as states struggle with their growing debts, investors could decide not to buy the debt of the weakest state or local governments,” which “would force a crisis, since states cannot operate if they cannot borrow.” The weakest states are not an eclectic assortment: “It is the long-term problems of a handful of states, including California, Illinois, New Jersey and New York, that financial analysts worry about most,” according to the Times. What that handful has in common is an exceptionally strong determination to defend and expand “generous” and “compassionate” government programs, a commitment that runs far ahead of their willingness to tax and budget for those programs, or negotiate sternly with the unions representing the public employees who deliver the programs’ services.

Californians can take scant comfort from the prospect that a blue-state meltdown may start elsewhere. (Illinois, for instance, appears to have dug itself into an even deeper hole.) No matter which other states have it worse, California faces years of austerity. According to a report issued in November 2010 by the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO)—California’s counterpart to the Congressional Budget Office—the state’s general fund is heading for a $20 billion shortfall every year until 2016, as far ahead as LAO cares to project. Since LAO does not expect general fund revenues to exceed $100 billion until 2015, these deficits would be more than one-fifth of the state’s budget for half a decade.

And that’s the good news. “We believe that our projections probably understate the magnitude of the state’s fiscal problems during the forecast period,” the report says. The picture would have been even bleaker if LAO had factored in the billions of additional dollars California must devote each year to fulfill pension and health care obligations to public employees who have retired or will in the future. (When and how the state will pay for those promises, and whether it will bend or break some—these were too murky for the agency to quantify and forecast.) LAO does estimate that the unfunded liabilities for these obligations amount to $136 billion. California’s “long-term fiscal liabilities—for infrastructure, retirement, and budgetary borrowing—are already huge,” the report states. “By deferring hard decisions on how to finance routine annual budgets of state programs to future years, the state risks increasing further the already immense fiscal challenges facing tomorrow’s Californians.”

Interest groups and journalists allied with the state Democratic Party adamantly favor tax increases as the centerpiece of any plan to restore California’s solvency. They are demanding, in effect, that Jerry Brown act like Pat Brown. Two weeks after the election, Los Angeles Times columnist Tim Rutten was giving the winning candidate history lessons about his father: “[K]eep in mind that one of Pat Brown’s first acts [as governor] was to push through unpopular tax increases that allowed him to simultaneously erase an inherited budget deficit and to increase spending on highway and school construction.”

Indeed, in the diary he kept during his first two years in office Pat Brown wrote, “I have nothing but contempt for those who say that no new taxes are necessary.” Brown’s deeds and words convinced Ethan Rarick, his biographer, that if the first Governor Brown were to confront California’s 21st-century fiscal crisis, he “would trumpet government’s positive role, insist that those who benefit the most from our society should pay the most, and set about enacting policies to create a public sector that was funded both fully and fairly. In short, he would raise taxes, especially on the rich.”

The planted axiom is that higher taxes—California’s are already among the highest in the nation—will get the state through the recession and recovery without further reductions or reorganizations of its public sector, hastening the happy day when things can go back to normal. The long-term structural deficits that appear endemic in the blue-state model of high taxes, big government, and strong public employee unions all argue, however, that “normal” is the problem. Americans are endorsing this proposition with the articles they write and the bonds they sell but also, more importantly, by decisions about where to build lives and enterprises. The first results from the 2010 census, released in December, show that the population of Texas, a state with no corporate or individual income tax, grew twice as fast as the nation’s overall population between 2000 and 2010. California grew at the national rate, meaning that for the first time since 1850, the census will result in no additional California seats in the House of Representatives. (New York will lose two House seats; Illinois and New Jersey will each lose one. Texas adds four.) More generally, as Michael Barone has calculated, 35% of the nation’s population growth since 2000 took place in the nine states that have no income tax, which together accounted for only 19% of the nation’s total population at the beginning of the decade.

From Dream to Delusion

It’s doubtful, in other words, that Jerry Brown or anyone else can govern California at the start of this century the way his father governed it in the middle of the last one. Pat Brown was a representative Democratic politician of his era: an unapologetic exponent of New Deal liberalism but also an unreflective one. Throughout his political career he defined himself as a “responsible liberal.” Like “compassionate conservative,” it’s a label that acknowledges the doubts your critics have sown with their principal accusation. “A liberal program must also be a responsible program,” Brown said in his painfully alliterative first inaugural address, “a reasonable, rational, realistic program. We must know how much it will cost and where the money is coming from. Benefits must be measured against burdens.”

After all this realism and calibration, however, the default option always remained government activism rather than restraint. Brown was never bashful about describing himself as “a big-government man,” and viewed the large deficit awaiting him upon taking office in 1959 as a mandate to increase state revenues.

A big part of New Deal liberalism’s strength was that it understood good government in a way that equated it with good politics. According to historian Martin Schiesl, for example, Pat Brown’s “final legacy was his generous and highly positive view of governmental power,” his faith in its capacity to “ameliorate some of the distressing aspects of modern society, provide all Californians with a measure of dignity, and assure for them a decent and durable standard of living.” This belief in the government’s ability to do good rested on accepting at face value what most Americans regarded as good. If New Deal liberals had any quarrel with the middle-class ethos of aspiring and acquiring, they kept it to themselves. The goal of active, ameliorative government was not to redirect or elevate the people’s desires, but simply to facilitate their pursuit of the good life as they understood it.

Pat Brown had the opportunity to implement this ideology in a time and place uniquely favorable to it. Kevin Starr’s multi-volume history of the Golden State emphasizes the enduring importance of the “California Dream,” a dream fully congruent with the New Deal vision. The state promised “the highest possible life for the middle classes,” Starr wrote, a “better place for ordinary people,” which meant “an improved and more affordable domestic life.” After his death Kathleen Brown said her father had believed in “the absolute destiny of California to grow.” California doubled in population between 1950 and 1970, surpassing New York while Brown was governor to become America’s most populous state. For every family that moved west, several who stayed behind shared the belief that the American dream, where the pursuit of opportunities is socially respected and governmentally encouraged, culminated in the California dream, the “conviction,” in Starr’s words, “that California was the best place in the nation to seek and attain a better life.”

But then the gears stopped meshing. The politics of liberalism and the sociology of middle-class aspiration became estranged and even antagonistic. As liberalism incorporated the agendas, grievances, and sensibilities of new social and political movements, liberals no longer wanted to foster the California dream but to attack it as a meretricious, hypocritical snare and delusion. Looking back on the 1950s from the vantage point of 1995, the New York Times critic Frank Rich delivered the indictment with a characteristically light touch:

The truth about the 50’s is that all the post-World War II fissures in American life were present and simply papered over—with the aid of racial segregation, the denial of equal social and economic status to women, the repression of homosexuals and the refusal to recognize crimes like wife battering and child abuse. It was inevitable that this phony nirvana would crack at the seams, as it did in the 60’s….

If America were such a picture-postcard of familial bliss in 1955, there would have been no reason to create Disneyland, which…opened that year—with one of its chief attractions being an idyllic all-American (and all-white) Main Street that could no longer be found beyond its gates.

Help-People Liberalism

Before the ’60s happened in the rest of America they happened—harder—in California. Pat Brown invested high hopes and huge governmental outlays in a “master plan” for a system of public higher education. It would be both accessible and excellent, training and edifying young people in ways that prepared them to join and strengthen the middle class. In a 1961 commencement address he encouraged students to energize American democracy by being more engaged with politics than the “silent generation” on campuses in the 1950s. “Thank God for the spectacle of students picketing,” he said. “At last we’re getting somewhere. The colleges have become boot camps of citizenship—and citizen-leaders are marching out of them…. Let us stand up for our students and be proud of them.”

Brown got more than he bargained for three years later, when students plunged the University of California’s Berkeley campus into turmoil after demonstrations by the Free Speech Movement. Its leader was Mario Savio, a 21-year-old philosophy major who had returned to school after volunteering for Freedom Summer in Mississippi. Savio’s most widely admired and quoted speech to the protesters revealed that in the course of acquiring a Berkeley education a student could also acquire the inability to distinguish between disenfranchised, second-class citizens demeaned by Jim Crow and menaced by the Ku Klux Klan, and undergraduates at one of the world’s most prestigious universities, on whom the taxpayers were pitilessly inflicting a tuition-free education:

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part! You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus—and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it—that unless you’re free and unless they’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

Pat Brown also championed state civil rights laws to end racial discrimination in employment and housing, hoping to foster a larger, racially integrated middle class living the California dream. The widespread belief that race relations in California were more congenial than in the South or the big cities back east was shattered in August 1965 when the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles exploded in a race riot that took 34 lives and caused $40 million in property damage, the equivalent of $278 million today. Nearly 14,000 National Guard troops pacified the streets, “roughly the same number of soldiers that the United States had used a few months before to put down an insurrection in the Dominican Republic,” Ethan Rarick notes.

Berkeley and Watts bewildered Brown. A prosecutor and attorney general before he became governor, he initially reacted to both convulsions by insisting on the need to uphold law and order. Inevitably, though, Brown’s ultimate reaction was that if public universities, civil rights laws, and social welfare programs had bequeathed mayhem rather than educational and racial progress, this only proved…the need for more public universities, civil rights laws, and social welfare programs. The adherents of responsible liberalism had no interest in pursuing questions about whether liberalism might have been responsible for creating (or at least was irrelevant to preventing) lawless disorder; the need for an ever bigger welfare state became, in effect, an unfalsifiable proposition.

Brown’s final three years in the governor’s mansion were also Lyndon Johnson’s first three in the White House. Despite getting along badly, the two men shared a governing philosophy. “[T]here is a difference between responsibility and timidity,” Brown said, “and we are resolved to be governed more by our hopes than by our fears.” The weekend after John Kennedy was assassinated, the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors briefed Lyndon Johnson on proposals JFK had sought for federal initiatives to reduce poverty. According to many accounts Johnson said, “That’s my kind of program. It will help people.” It would be difficult to imagine a less rigorous criterion for launching or expanding social programs.

A serious difficulty with help-people liberalism is that it is content to judge itself solely on the basis of the immediate impact it has on the people in the direct center of the helper’s field of vision. The potential for a government program to inflict collateral damage on third parties by diverting resources from productive uses, or to create new problems for the intended beneficiaries, is discounted because those people and problems lie beyond a tightly constricted horizon. This disposition was the basis for the complaint by David Stockman, President Reagan’s budget director, about liberalism’s “single-entry bookkeeping,” which treated benefits bestowed here as if they had nothing to do with costs imposed there.

The fecklessness that fails to consider second- and third-order consequences is not just fiscal, however, but moral. Rarick tells how Pat Brown, in his final days in office, commuted a convicted rapist’s life sentence, then felt “anguish” years later when he learned that after being paroled the man had raped again, this time murdering one of his victims by stabbing, strangling, and ultimately drowning her. Brown’s hopes for rehabilitation had triumphed over any fears he had about recidivism, and caused a private citizen entitled to expect that her safety would be an overriding government imperative to die in terror and agony.

Father and Son

Public personas less alike than Pat and Jerry Brown’s are difficult to imagine. Pat Brown was a politician like Hubert Humphrey and Bill Clinton, one who never saw a hand he didn’t want to shake or a room he didn’t want to work. Jerry Brown came across like Adlai Stevenson and Eugene McCarthy, men who got into politics in order to demonstrate their superiority to it. He once explained that what most struck him about the politics that was all around him when he was growing up was, “[t]he grasping, the artificiality, the obvious manipulation and role-playing, the repetition of emotion without feeling—particularly that.” In 1996 he said politics, “a power struggle to get to the top of the heap,” is “based on illusions.”

Californians who, even now, aren’t sure what to make of Jerry Brown are in good company. Pat Brown told a journalist during his son’s first term as governor, “He knows me a lot better than I know him. I guess I’m just more outgoing than he is. Sometimes I’m not sure I really know Jerry.”

During Jerry Brown’s early years in politics many journalists theorized about the relationship between the back-slapping father and his aloof son. The resulting articles were mostly speculative rubbish, made worse by psychobabble. One of the few still worth reading is a 1976 New York Review of Books profile by Garry Wills, “The Anti-Papa Politics.” Pat Brown, Wills wrote, was “a sentimentally good-natured man, but one who resisted political pressure poorly.” His son, by contrast, “has a genuine compassion for the poor and mistreated; but he seems to feel it best from some height of ordered action.” Wills concludes that the younger Brown’s “real guiding principle” is the determination “to repeat his father’s career without being like his father.”

Father and son differed in ways more important than their demeanors on rope-lines. In his first inaugural address Pat Brown said “the explosive growth of our population and economy” was “magnificent,” and pledged “a confident, pioneering leadership, ready to welcome growth, pursue its promise, and prepare for tomorrow.” Those preparations meant, above all, ambitious government capital projects. California built over 1,000 miles of freeways during the eight years Pat Brown was governor. His proudest achievement was the California Water Project, a system of dams and aqueducts that brought water from the state’s northern rivers to Central Valley farmlands and dry, southern metropolises.

The environmental movement, nascent when Brown left office in 1966, came to view such infrastructure as an accommodation, and therefore a capitulation, to the rapacious growth rendering California, America, and the planet uglier and less inhabitable. Whereas Pat Brown celebrated that growth as California’s destiny, Jerry Brown treated it like an affliction. Joel Kotkin points out that one fifth of state spending under Pat Brown was devoted to capital outlays; only 5% when his son was governor. Jerry Brown’s attitude to roads, dams, and infrastructure in general reversed not only his father’s inclination but the whole Field of Dreams formula: if you don’t build it, they won’t come. In California, Inc., a book by Kotkin and Paul Grabowicz published in 1982, one of Governor Brown’s advisors tells them:

Jerry’s attitudes developed all the years watching the political activity around his father. This build, build, build thing was just prevalent. He could remember seeing the cement builders…applauding loudly about paving over the state. It all began a real questioning of the values of the Democratic Party, questioning all the programs and the money.

Far more than his father, Jerry Brown governed California as if aware of the law of unintended consequences. The problem was that environmental crusades could lead his administration to emphasize consequences harmful to fish and birds over those affecting people. Brown appeared to have exhausted Californians’ patience and ruined his once-promising political career in 1981 when he refused to allow the California Department of Food and Agriculture to use helicopters to spray Malathion, a chemical agent routinely used in other states, on farmland infested by the Mediterranean fruit fly. Brown relented only after foreign countries began refusing, and the federal government threatened to quarantine, California produce. The veteran California journalist Peter Schrag’s verdict on Brown’s conduct during the med-fly episode was that he had “exaggerated the health hazards of every technological attempt to control the environment.”

Being Different

Wills’s contention that Jerry Brown’s “guiding principle” is to avoid being like his father is plausible, but leads to a deeper problem: not much guidance is provided by the “principle” of being different from someone else. Forty years after Brown was first elected to statewide office, the Tao of Jerry resists comprehension. Even the journalist Roger Rapoport, who told an interviewer three years ago, “I really like Jerry Brown,” wrote a sour conclusion to California Dreaming: The Political Odyssey of Pat and Jerry Brown (1982), an admiring book on the Browns at the end of the younger man’s second term as governor:

Too often Jerry starts out in one direction with great fanfare, has second thoughts, and ends up following an entirely different course, all the while pretending he never changed his initial position. And while this sort of zero-based thinking may suit a philosopher, real people with real problems inevitably demand more programmatic clarity from their political leaders, as well as a greater commitment to following through on last year’s good ideas.

His pivots, however, have ended up helping Brown. The innumerable contradictory, gnomic, and elliptical things he has said over his career have forged a sturdy Teflon armor for him. Journalists and voters dismiss utterances that would damage any other politician as just further instances of Jerry being Jerry.

Brown’s unusual approach has also inoculated him from the charge of being a hack. Brown works hard to convey that he—unlike his father, unlike the vast majority of politicians—doesn’t especially care whether you like him or not, which earns him the benefit of the doubt that he’s telling you what he really thinks rather than what you want to hear.

Furthermore, Brown cares even less about making sense than he does about making friends. When challenged about taking positions diametrically opposed to ones he had taken in the past, Brown turns the question around in a way that makes his variability empirical and flexible, and the questioner’s concern with consistency narrowly dogmatic. “You grow. You learn from mistakes. Positions evolve,” he blithely told one reporter in 1992 who asked about his many reversals. “You experiment…. You can’t keep repeating.”

During his first eight years as governor Brown often said, in a similar vein, that you steer the canoe forward by paddling sometimes on the left and sometimes on the right. He paddled on the right enough to anger more than a few Democrats. On 12 occasions during his first two terms as governor the Democratic legislature overrode his vetoes; no governor of either party has had a veto overridden since. It would have been no surprise to hear Ronald Reagan say:

Government is not the basic reality. People are. The private sector. And government is just a limited power to make things go better. Now we’re inverting that, and government is all-pervasive. Every time you turn around there’s government. I think that’s not part of the American character.

The governor who said that, however, was not Pat Brown’s victorious opponent, but Brown’s son. In connection with their observation that Jerry Brown’s budget cutting “was more vigorous and successful than Reagan’s,” Kotkin and Grabowicz cite one disaffected liberal who said, “When Jerry Brown talks about lowering expectations, he is really talking about lowering expectations for the poor, the mentally ill and the disabled.” Brown would campaign for president in 1980 as an advocate of a balanced budget amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and then in 1992 as a champion of the flat tax.

Brown paddled left and right with particular vigor in 1978, the year he ran for reelection to a second term and the voters enacted Proposition 13, which cut property taxes deeply and made future tax increases more difficult. In the weeks before the June 1978 primary, where Proposition 13 was the main event, Brown opposed it categorically, calling it “a consumer fraud, expensive, unworkable and crazy.” Yet 13 received 65% of the vote on a day when 69% of the eligible voters went to the polls, “an extraordinary turnout for a primary election in a nonpresidential year,” according to Peter Schrag. Brown’s Republican opponent, Attorney General Evelle Younger, thought the incumbent was doomed after opposing such a popular measure. Proclaiming himself a “born-again tax cutter,” however, Brown maneuvered so quickly to establish his determination to implement the ballot proposition successfully that a poll before the November election showed that a majority of Californians thought Brown had favored the proposition all along. “We have our marching orders from the people,” Brown said shortly after the June election. “This is the strongest expression of the democratic process in a decade.” By contrast, Pat Brown, a big-government man who never saw much need to paddle on the other side of the canoe, bluntly told an interviewer in 1978 that Proposition 13 had “cut the guts out of a great government.”

Strange Sabbatical

Brown’s defeat in the 1982 senate election started a long, strange sabbatical from public life that nearly every observer thought would be permanent. After leaving Sacramento, Brown practiced law, spent a few months studying Zen in Japan, and briefly tended to the sick with Mother Teresa in India. In 1989 he returned to politics, sort of, winning the chairmanship of the California Democratic Party. In order to overcome convention delegates’ misgivings about his commitment to the work, Brown “spent months on the telephone convincing Democrats that he was serious” about “the often plodding administrative tasks of running a state political organization,” according to the New York Times. Brown quit the job in 1991, saying he found the “nuts and bolts” aspects of politics boring.

His strident and obviously hopeless run for the presidency in 1992 threatened to turn Brown into his generation’s Harold Stassen, minus the redeeming sense of dignity. By mutual consent Brown had little public involvement with his sister’s 1994 gubernatorial campaign, declaring himself a “recovering politician” who had already done “the hack politics.” Brown’s political venues became an activist group, We the People, and a call-in show on the left-of-Lenin Radio Pacifica. An article Brown wrote for the Earth Island Journal in 1996, “How to Avert Global Calamity,” condemned Orlando’s Disney World in terms that make Frank Rich’s views on Disneyland seem temperate:

Could this be the ersatz answer to the awesome challenge of the age? Create a perfect, corporate reality that provides crime-free, clean fun. Like the triumph of McDonaldization, Disneyfication of existence promises certainty, predictability and wonderfully sanitary conditions. Few infantilized and soothed people will worry about soil loss or global warming or an overcrowded world haunted by hungry people.

That same year Brown gave an interview where he was asked whether his “unrelievedly grim” 1992 presidential campaign hadn’t been excessive. To the contrary, Brown said, “I don’t know that I was angry enough. I think if we’re talking about indignation at injustice and deception, I would say that I really haven’t attained the level of anger appropriate to the evil that is engulfing the country and the world.”

It’s difficult but important to remember that these reflections are taken, not from the Unabomber manifesto or a Rolling Stone interview with some self-enthralled, self-medicated artiste, but from the public discourse of a man, approaching his 60th birthday, who had governed the largest state in the Union for eight years. They do not, moreover, sound like the remarks of a prospective candidate for any future office. But in 1997 Brown decided he had recovered from being a politician as much as he cared to, and announced his candidacy to be mayor of Oakland. (He reentered politics, coincidentally or not, the year after Pat Brown died.) Brown won the 1998 election, was re-elected in 2002, and then won another of his father’s previous jobs when he was elected attorney general in 2006.

A Very Good Hater

If Jerry Brown had decided against resuming a political career, his slender legacy would have been dominated by the idiosyncrasies he indulged and the promise he never fulfilled. It would have been marked, above all, by his inability (shared with the Democrats of his generation) to fashion a coherent, workable ideology to succeed the “responsible liberalism” shared by Pat Brown and Democrats of his generation. As opaque as he can be in general, Jerry Brown’s aversion to the style and substance of New Deal liberalism has never been hard to read. “As a politician,” Garry Wills wrote, Brown “is a very good hater.” He clearly hated interest-group liberalism—the deals, the compromises, and the pursuit of narrow, selfish advantages cynically dressed up in the language of social justice. “Brown shows an open contempt for political hacks,” Wills observed, “and gets furious at their attempts to influence him.”

Brown’s low opinion of the pursuit of self-interest applies to citizens outside the political process as well as to players in the game. His scorn for Disney World’s crime-free and sanitary conditions is connected to disapproval of the infantilized customers who flock to that ersatz experience, and who demand something like it in the Real World when they come home from vacation. In 1986 three of the justices Brown had appointed to the state supreme court were defeated in a popular retention election and forced off the bench. The most controversial was chief justice Rose Bird, appointed by Brown despite her lack of judicial experience. During her nine years on the court Bird voted to overturn each of the 61 death sentence cases that came before her. She was, apparently, not adroit enough to reposition herself during the 1986 election as a born-again crime fighter. After Bird died in 1999 Brown described her as “perhaps the last champion of a more sensitive and empathetic perspective” on capital punishment.

Harold Macmillan once said that what gave him the most satisfaction about his long career in British politics was the sight of “a line of family cars, filled with fathers, mothers, children, uncles, aunts, all making their way to the seaside.”

Ten years ago most of them would not have had cars, would have spent their weekends in the back streets, and would have seen the seaside, if at all, once a year. Now—now—I look forward to the time, not far away, when those cars will be a little larger, a little more comfortable, and all of them will be carrying on their roofs boats that they may enjoy at the seaside.

It’s easy to imagine Pat Brown, whose freeways and aqueducts brought the California dream within reach of millions, taking similar pride in facilitating humble but widespread aspirations. It’s impossible to imagine Jerry Brown feeling the same way. The “political leaders who most intrigue him are Mao Tse-tung and Ho Chi Minh,” Wills wrote. “It is the ability to organize a people to puritanical effort and standards that he admires.”

During his recent term as attorney general, Brown threatened to file suit against municipalities whose zoning and development policies encouraged new subdivisions of single-family homes, rather than the high-density housing developments clustered near mass transit lines that Brown favors. Joel Kotkin points out that natural science hasn’t settled the question of whether the type of restrictions Brown favors would in fact reduce a metropolitan area’s carbon footprint. (For one thing, when Americans in general and Californians in particular say they support mass transit, what they mean is they support other people using mass transit, other people who will unclog the roads for the rest of us by riding trains and buses. When nearly everyone feels this way, however, nearly everyone sits in the same traffic jams watching heavily subsidized, half-empty trains roll by.) The political science is straightforward, however: four out of five Californians would rather inhabit single-family homes, the most basic element of the California dream, than live in apartment buildings, according to a poll by the Public Policy Institute of California. Indeed, the Los Angeles Weekly discovered that many of the city’s most prominent advocates of “smart growth” reside in single-family houses so far removed from the nearest mass transit as to make driving a car their only transportation option.

It’s just as well that the Democrats of Jerry Brown’s era who found New Deal liberalism squalid and ignoble never came up with a policy agenda to implement their cultural critique. It’s very difficult to imagine the set of laws and regulations that would have effected Americans’ disembourgeoisement, and even harder to envision the successful political campaign that would have secured support for it. The worst thing even Frank Rich had to say about Disneyland in a recent column was not that it distracts us from our society’s pervasive bigotries and pathologies, but that too many Americans now lack the economic wherewithal and security to go there.

What Comes Next

Jerry Brown won’t be remembered, then, as the Democrat who figured out What Comes Next. Instead, he finds himself in his eighth decade with a surprising opportunity to clarify whether What Came Before can or can’t work. One of the virtues of American federalism is that it allows for 50 answers, rather than just one, to the question of whether government should be expensive and expansive, or cheap and bare-bones. The especially precarious finances of states that have embraced the former approach, like California and New York, suggest that the blue-state model, whatever its abstract virtues, suffers from a severe practical defect: it’s doomed if the people who live under it, accepting or even demanding its benefits with their votes, are unwilling to pay its bills. That will be the result if they’re selfish and irrational, but also if they have plausible doubts that the government hasn’t been zealous, or even serious, about providing its benefits fairly and efficiently, calling into question whether what government costs significantly exceeds what it requires.

For Pat Brown Democrats, within California and beyond, the story is tragic but simple—responsible liberalism got mugged by irresponsible conservatism. Californians were enjoying excellent public services, confident that the corresponding taxes were levied fairly and necessarily, when gluttonous corporations and conservative ideologues beguiled the voters into forsaking paradise by passing Proposition 13. Ever since that Fall, California’s vital programs have been chronically underfunded, as state and local governments have temporized from one fiscal crisis to the next.

It’s a plotline with serious holes, as we say in Los Angeles. It’s not clear, for one thing, why voters who had so many reasons to be satisfied with the status quo were so susceptible to conservatives’ appeals to the baser angels of our nature. Nor does it make sense that once the voters committed this huge blunder, and its dreadful consequences were manifest, neither they nor the legislators ever seriously entertained the idea of reversing or even modifying it. Finally, states that never really had a tax revolt, like New York and Illinois, are facing long-term fiscal prospects as daunting as California’s, suggesting the blue-state model has essential flaws, rather than merely ones attributable to the accidents of California politics.

Given the structural deficits now faced by so many European social democracies, Jerry Brown will get to close his political career by weighing in on a question of great importance beyond California’s borders and America’s shores. Can the proposition his father considered self-evident—that activist government can ameliorate distressing aspects of modern life, and assure people a decent, durable standard of living—be made to work in the long run? Or must it succumb to the fatal flaws of disposing citizens to abuse government benefits by taking them for granted, and government to abuse taxpayers by taking them for granted?

There’s no prospect Governor Brown will solve this dilemma by organizing Californians to puritanical effort and standards. If the final chapter in his biography is to be a happy one, he will, instead, persuade the people to pay for what they get from government and give them compelling, tangible reasons to believe that what they get is worth all that they’re being asked to pay. Though he’ll paddle left, and paddle right, it’s no longer just a question of whether the ship will remain on course, but whether it can stay afloat.

May 27th, 2011 at 11:58 am

[…] Don’t take my word for it — today we feature a staggeringly insightful article, The Tao of Jerry Brown, from Claremont scholar William Voegeli that appears in the latest addition of CRB (reprinted with […]